Heat Wave: How do we unchain the Filipino cultural economy? (Part 1)

Share

Note: This is the first in a series of essays by Rexy Dorado, co-creator of the Maharlika comic series on the Maharlika substack.

Greatness takes time. And I don’t mean that in the motivational coach kind of way—I mean it in the most dry and pragmatic sense. If you’re making creative work, chances are you need to produce a lot of output, and before you get to your masterpiece, you’ll need thousands of hours of work and practice.

If you’re gifted in a medium that allows for a one-person team, that’s already hard enough. You have bills to pay, and if you have a day job, it will consume at least 40 of your waking hours each week (if you’re lucky) plus commute and residual stress. If you’re one half of a duo, like me and my artist partner John Ray in Maharlika, then you start dealing with the problem of a double-coincidence of free time and focus. If you’re aspiring to be a filmmaker, then you scale that problem exponentially to 10 or 100 people who need to drop everything to execute a creative vision.

All of that time costs money. As a creative in a capitalist society, money translates to being able to say “no” to other opportunities that help you pay your bills. I’d love to live in a socialist paradise where everyone has Universal Basic Income and full freedom to allocate their hours to the project they believe in, regardless of the economic factors—but we live on Earth in 2024. I’ve been privileged enough to have worked on things over the past few years that allow me to have more control of my time, and pay John fairly so he has the ability to say no to other things and work on IP that he co-owns. But even then, we are constrained by the limits of our own personal budgets.

South Korea subsidized that time with a commitment of 1% of the government budget as early as 1999, and it worked. After several long decades of patient investment, Hallyu, or the Korean wave, is an indisputable champion when it comes to worldwide cultural impact. In Japan, a century-long investment in manga has produced a gigantic anime and manga industry that has spawned some of the most widely-loved stories in the world. With the fall-off of Star Wars and the Marvel Cinematic Universe, I struggle to think of stories and worlds that have as large and loyal a following as Japan’s One Piece, or even new-gen juggernauts like Jujutsu Kaisen, Demon Slayer and (my personal favorite) Chainsaw Man.

This capital, whether it comes from upfront investment that eventually pays off, or a well-oiled machine that understands deeply how to find and market gold, has unlocked—you guessed it—time. Time in the form of full teams of manga assistants supporting the weekly release of your favorite Shonen Jump title, or hundreds of animators hard at work on the next piece of breathtaking sakuga.

So how do we unlock more time for Filipino creators to work on original content? That’s the question that this series of essays will focus on. I would be lying if I promised an answer; there are far smarter people than me who have been working on this problem for far longer. So take this as what it is: a high-level and informal exploration of the current landscape of the Filipino cultural economy, from what I hope is a unique and helpful perspective.

That perspective is as someone who, on one hand, is a writer of comics and short stories; and on the other hand, is a producer, investor, and business builder in the Filipino media space. As the co-creator of the Maharlika, I’ve seen the struggles of building a new story from scratch in the comics format. And as the co-founder of Kumu, I’ve raised $100m for Filipino media, generated $100m+ in revenue with Filipino content, and paid out similarly significant chunks to creators of Filipino media. I’ve also been an investor and advisor to companies working on music, books, gaming, and podcasts. At the very least, mine is a perspective that’s fairly unique, with shards of inside insight in a few sectors—though I wouldn’t claim it as representative.

Perhaps just as importantly, this comes from the perspective of a fan: someone who loves great stories in all mediums and is hungry to see more great Filipino creative work out in the world.

I don’t have this essay series fully structured ahead of time, but we’ll start with an exploration of the current state of different segments of Filipino media, including comics, film, music. Our first stop is the movies.

Is Filipino film hitting an inflection point?

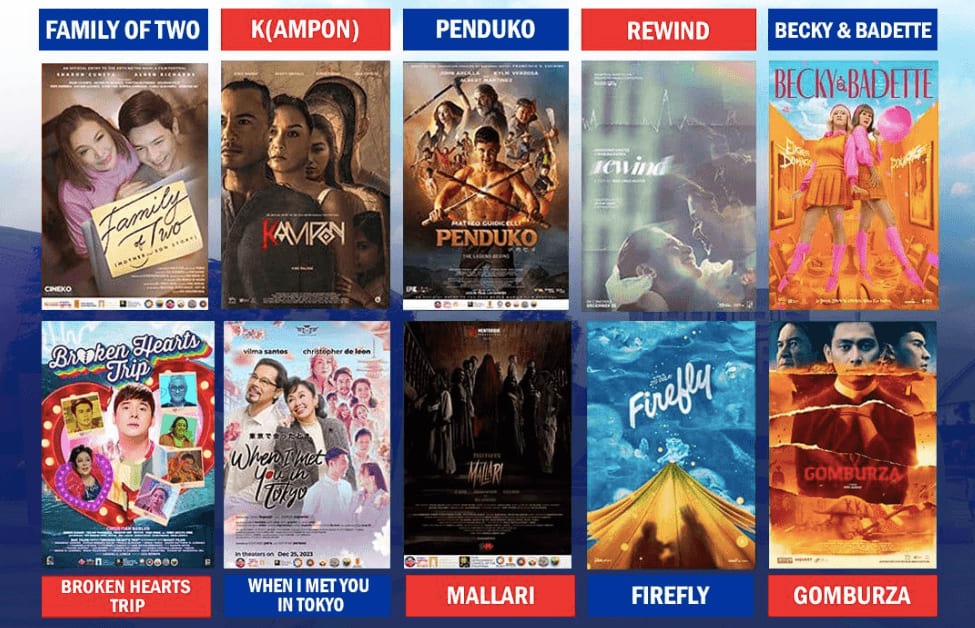

In 2023, the Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF) celebrated a considerable achievement: 1 billion pesos, or a bit less than US$20 million in box office sales. As someone who released a movie in MMFF 2021, I can tell you that this is a huge step up: I would estimate that most MMFF films that year struggled to generate even five figures USD in revenue during their opening week, and the spike of COVID cases post-Christmas killed any possibility of recovering from a slow week 1.

So is this cause for celebration? Absolutely. Does it solve our problem of needing an economic engine for original Filipino films? Not even close. The vast majority of that revenue—between 80-90% of ticket sales—went to a single film, Rewind. Gomburza took another 5%, according to Wikipedia’s (as of writing) uncited estimates. Let’s guesstimate ~$2 million left between the remaining 8 films, and that gives us an average of $250,000 gross per film.

From my personal experience, a feature film in the Philippines usually costs around $200,000, sometimes lower, sometimes as high as $500k-1m. So when you take out the chunk of money that goes to the theater and to taxes, it’s not hard to imagine only 2-3 out of the 10 MMFF entries making their money back on cinema proceeds. For the rest, they can earn back their budget from streaming deals, but as of a year or two ago, it wasn’t uncommon for these deals to land far below the cost of production. In the golden age when Netflix was investing heavily in growth, $500k-1m+ domestic deals were more common, but that window has passed UNLESS your IP has strong international appeal.

(Note: When I bring up numbers, assume that I’m giving a range based on anecdotal sources I’ve asked over the past couple of years, and it’s not necessarily referring to any particular movie which may be well under or over the norm.)

So even in a record year, it’s a challenge to just break even—and we’re only talking about the 10 films out of however many that were part of MMFF, and were thus shown across all theaters nationwide by the force of government mandate. These are the top movies with the widest domestic distribution. As I’m writing this, I also suspect that I’m giving pretty generous estimates—there’s a likelihood that many movies are making less money on larger budgets.

The way you respond to a challenge like this is by de-risking. If you’re a big studio, that can take a few forms: One, lowering incremental costs by leaning on your fixed investments: sets and equipment you already own, staff that are already employed with fixed salaries, talents that are on fixed retainers and no to minimal per-project fees. The other way is by maximizing your odds of earning money. In the global film industry, that usually takes the form of star power or IP. The problem with the latter is that there isn’t a lot of Filipino IP with built-in fanbases, aside from Darna and the FPJ franchise—but let’s put a pin on the topic of IP for now. Lastly, large studios have the ability to loss-lead when necessary: in other words, to lose money on the actual film, but leverage that film for growth in other business lines, such as events, merch, or their own streaming business (see: iWant).

If you’re a smaller film studio, you don’t have the option of leaning on economies of scale, but technology has allowed for small teams to create films at a much lower cost. Some of the best Filipino films of the next decade might come from small teams that are able to squeeze out a lot of resonance from a small budget. If you can execute a film at $50-100k, it will be much easier to earn back your investment from a streaming deal or a successful cinema run; if you can lower it even further, then your risk can go down to as low as zero, excluding sweat and tears. Avid Liongoren’s Saving Sally was a classic example of this, earning ~$500k gross from a budget of ~$200 (no “k”) and a lot of hard work and stress.

This playbook is much easier (though by no means easy) to execute if you’re creating a story that’s grounded in the real world and takes place in as few locations as possible. It’s much harder (though by no means impossible) if you’re creating something with a lot of action, magic, or other elements that can threaten to blow up the budget.

For the latter category, it becomes more important to de-risk through creativity on the revenue side. The recent success of the Filipino-led Kickstarter campaign of The Lovers is, to me, the most exciting example of this, generating $410k in revenue to fund the animated production by pre-selling digital assets, posters, figures, and… Sirena’s bathwater? If managed well, this amount can drastically reduce the risk of a failed production (though, if the final product lives up to the quality we’ve seen so far, they might not need to worry too much about that risk!)

This is a good time to revisit that pin that we placed on the subject of I.P. Formats such as comics and novels aren’t only valuable as proof-of-concepts for more “premium” formats such film and TV. In fact, I’m a believer that in the long term, audiences will gravitate to consuming stories in comics or webtoons form over movies. But they do allow for valuable proof-of-concepts regardless, if the creative vision includes a downstream adaptation to a format that costs more to produce.

This brings us to our next stop: comics, manga, and webtoons.

To be continued.

![Ilustra: Daybreaker by Tori Tadiar [English, Softbound]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/9781368089937.jpg?v=1769050132&width=533)

![Philippine Spirits Mythica Obscura by Karl Gaverza [English, Softbound]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/PhilippineSpiritsMythicaObscura_U.S.LimitedEdition.jpg?v=1753247631&width=533)

![Maharlika Volume 1 by Rexy Dorado & John Ray [English/Softbound]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/374578393_624068046540928_3600289409739988656_n.jpg?v=1763014205&width=533)

![Filipino Children's Favorite Stories: Fables, Myths and Fairy Tales (Favorite Children's Stories) [English/Hardcover]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/91LnoJqa3aL._SL1500.jpg?v=1764825238&width=533)

![Maharlika Volume 2 by Rexy Dorado (Writer) & John Ray Bumanglag (Illustrator) [English/Paperback]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/MaharlikaVol2Cover.jpg?v=1743482901&width=533)

![My First Book of Tagalog Words: An ABC Rhyming Book of Filipino Language and Culture By Liana Romulo Illustrated by Jaime Laurel [English/Filipino, Hardcover]](http://hottropiks.com/cdn/shop/files/91odClO4HGL._SL1500.jpg?v=1764825238&width=533)